Our political life, much like our social and economic life, has become one of immediacy; where the instant gratification of positive headlines and temporary poll boosts reigns supreme over slow-burn projects. “The great irony of our time”, says anthropologist Mary Catherine Bateson, “is that even as we are living longer, we are thinking shorter”.

Short-termism is baked into UK policymaking, epitomised in a Treasury calculation called ‘discounting’. Hidden behind technical economic language, what discounting does at a base level is presume that money, benefits, or costs in the future will be worth less than they are today. As a standard practice, UK government departments will ‘discount’ by 3.5% – but benefits potentially accrued after 60 years are deemed unworthy of consideration, making the effective discount rate at this point 100%. This formula has been used to back out of expensive renewable energy projects, such as the tidal lagoon energy project in Swansea Bay , which was shot down via comparisons to quicker and more ‘cost effective’ options such as nuclear (which for all its benefits has a whole host of problems in the long-term – see below).

This structural short-termism means that the UK falls behind many of its wealthy peers, ranking a measly 45th in interdisciplinary scientist Jamie McQuilkin’s Intergenerational Solidarity Index, which measures how well societies measure in a variety of environmental, educational, and economic factors.

The importance of the present

It has been said by many political commentators that current liberal governments need to make people feel tangible change in their lives to stem the rising tide of populism, and that they need to do this fast. While this is undeniably true, ignoring the long-term future is no longer an option. Long-termists often talk about the fact that we are living on a ‘hinge-point’ of history, walking a tightrope between the existential emergencies of climate breakdown, rapidly aging populations, and pandemic unpreparedness, to name a few. Particularly in relation to the climate crisis, real attempts to diffuse such time bombs must occur within the next few years – at a push, decades – or our efforts will become all but obsolete. In this context, acting in a way that takes into account the needs of future generations becomes – quite paradoxically – strikingly urgent.

The power of thinking in the long-term is that it allows us to sit at the precipice of our comprehension. Expanding our horizons towards the far future – considering the next decades, centuries and even millennia – forces us to go against all our initial instincts and immediate responses.

Long-termism in action

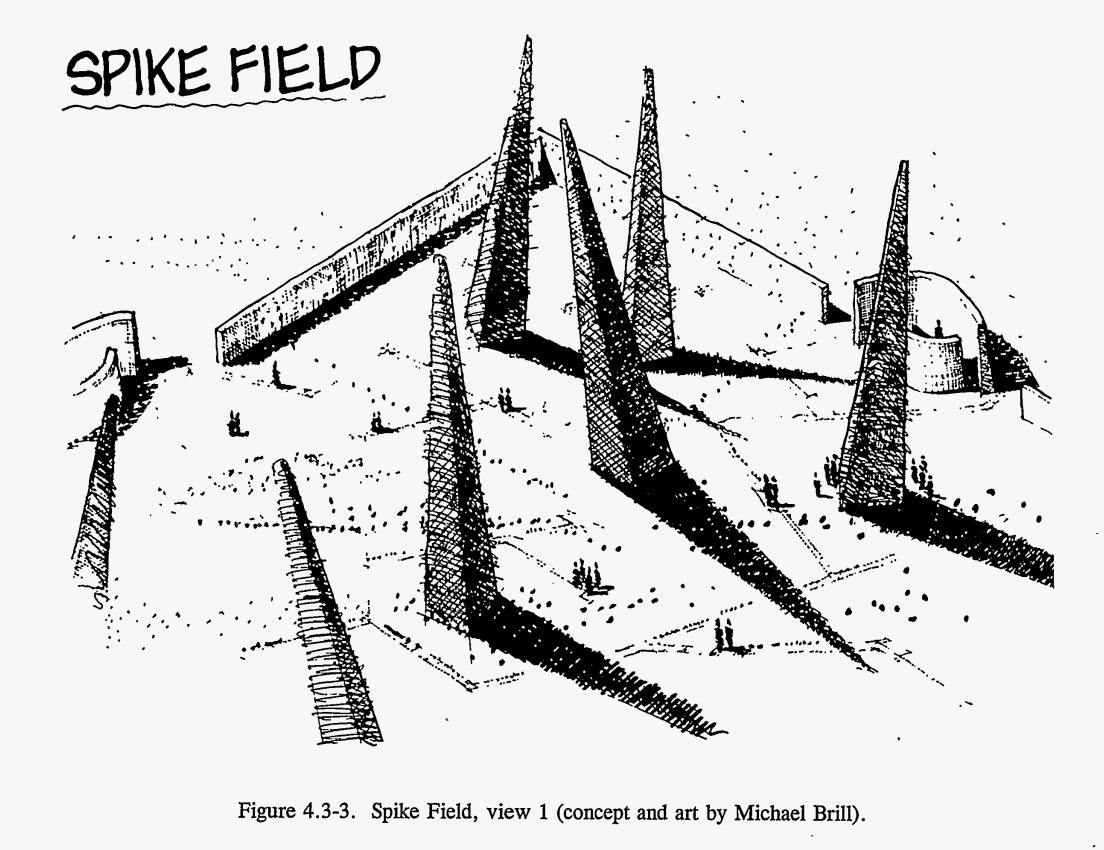

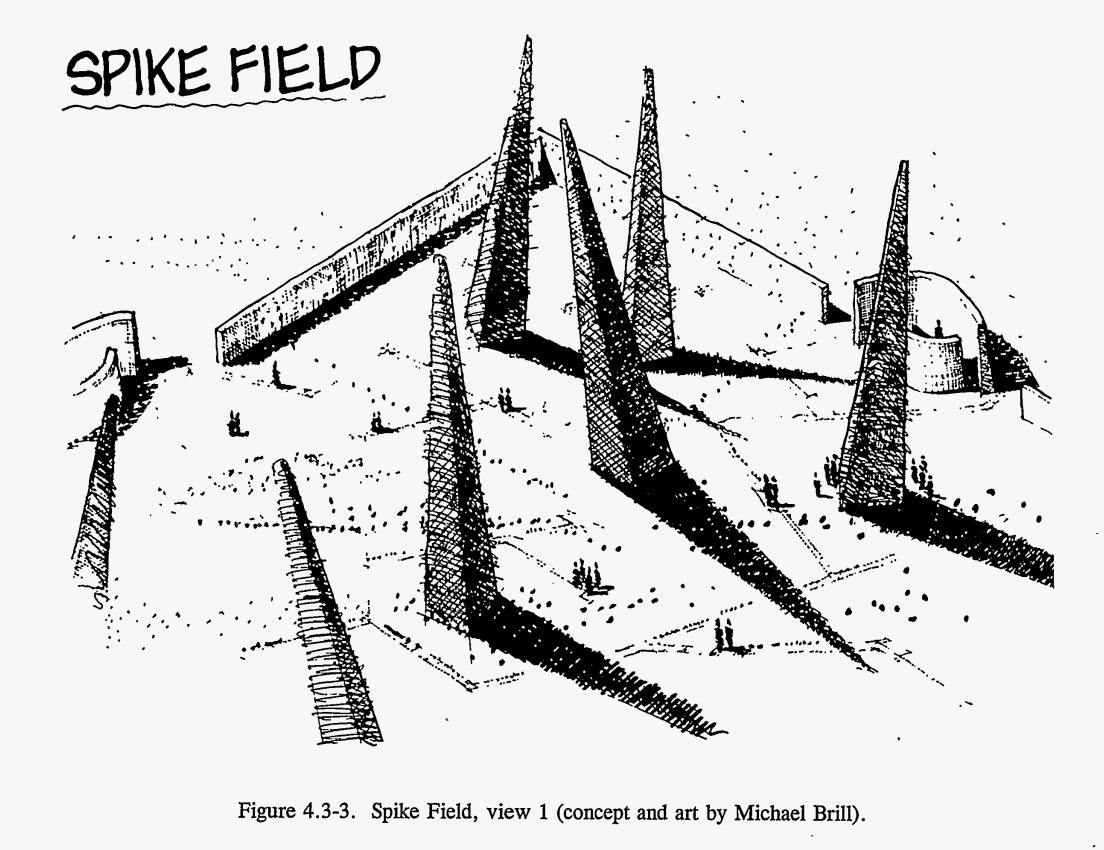

Operating outside our normal temporal frame requires bold and innovative thinking to solve problems that might not even have been conceptualised yet. For example, there is a whole group of thought dedicated to considering how we may convey the danger of radioactive nuclear waste to far-future generations. How can the presence of an invisible mortal danger, that is buried deep into the ground, be communicated to those living tens of thousands of years in the future? How do we transmit such a vital message to people whose lives will be unrecognisable to us – who may not share the same culture, the same language, even the same scientific knowledge? Many wild and wonderful ideas have been floated, including creating an atomic priesthood to pass down nuclear knowledge, selectively breeding cats to glow in the dark when near radiation, and erecting a field of spiked structures where the waste is stored to deter drilling.

Long-term thinking? The nuclear waste spike field. Concept by Michael Brill; Drawing by Safdar Abidi. Source: U.S Department of Energy: Site markers – Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP)

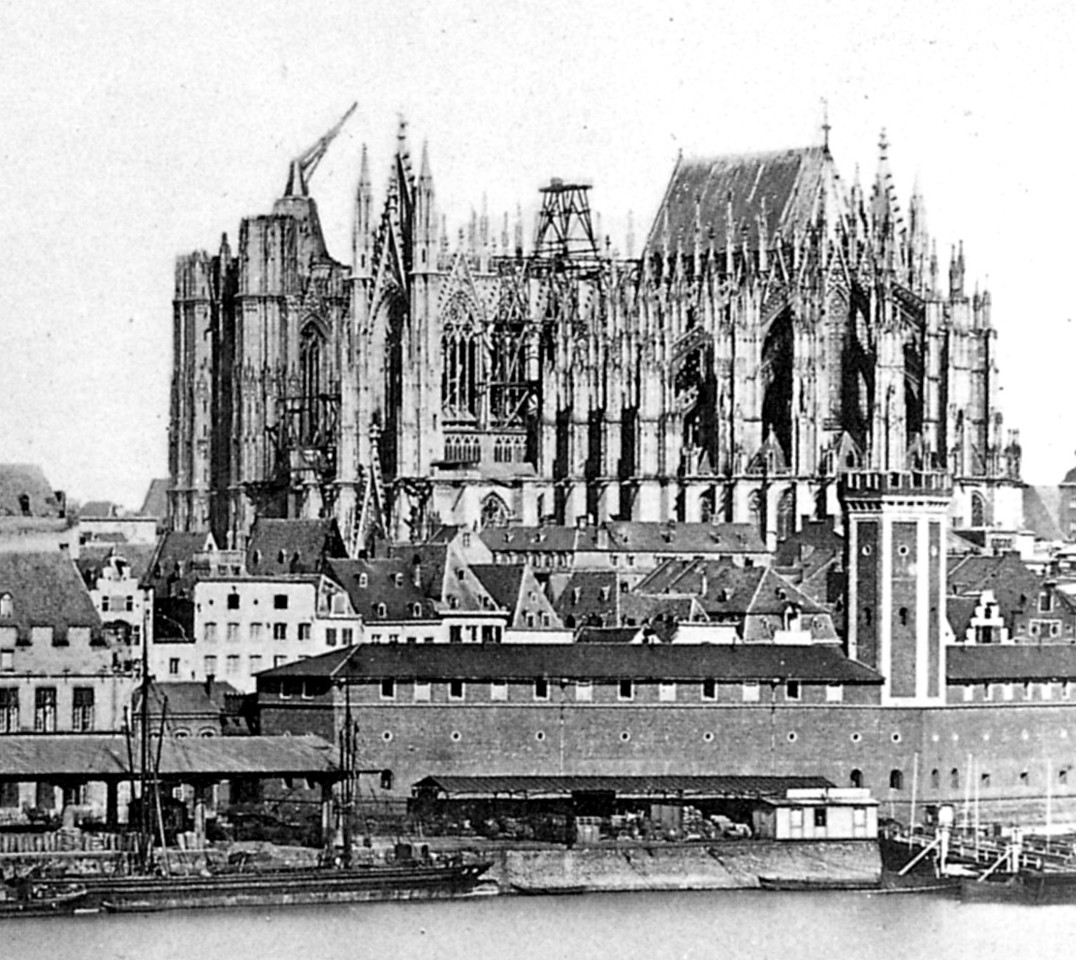

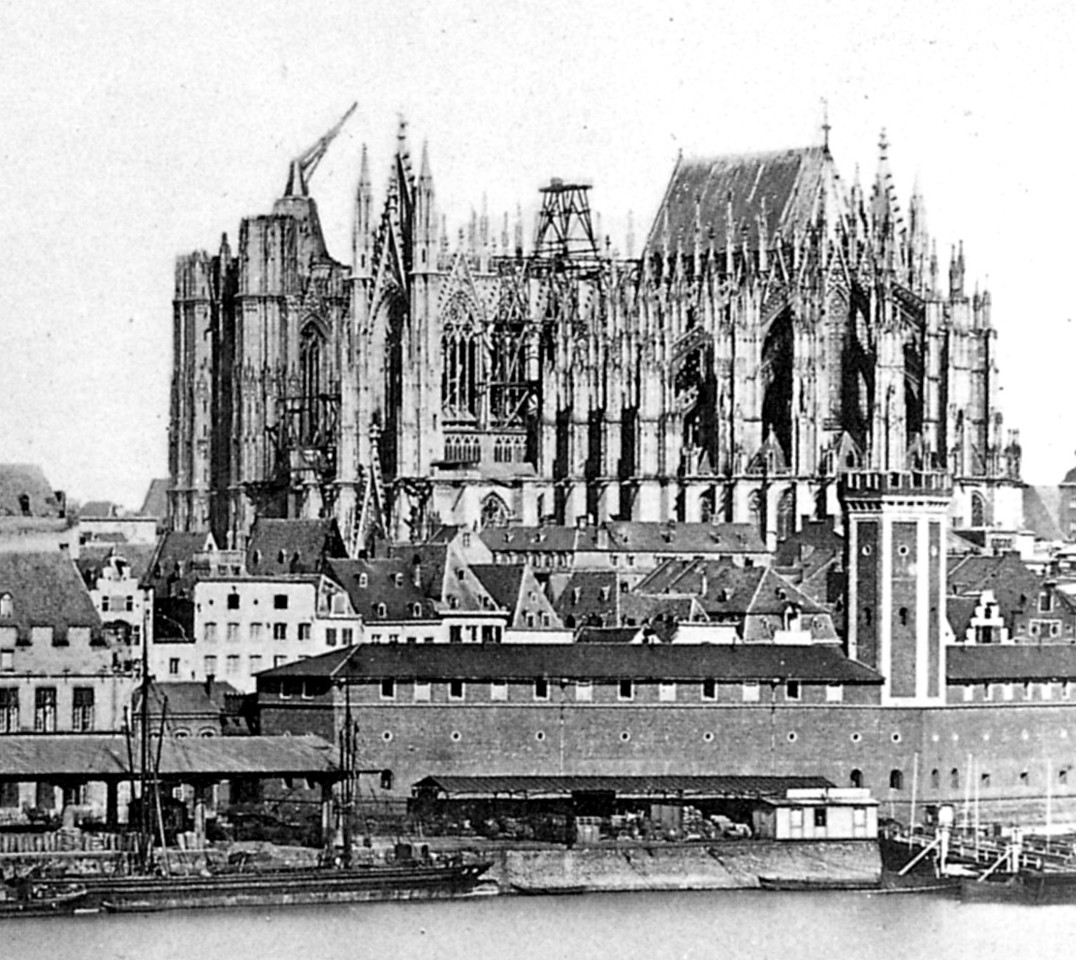

Long-termism is also more than just a thought experiment or imaginative exercise – what anthropologist Vincent Ialenti terms a kind of “calisthenics for the mind”. Many great practical feats have been made possible through baking this philosophy into their design. In fact, long-termism is often called ‘cathedral thinking’ in reference to the medieval architects, stonemasons and artisans who laid their plans and began construction of structures which they would never see completed in their lifetime.

Long-term thinking in the form of the unfinished Cologne Cathedral, which took 632 years to build. Source: Rheinpanorama 1856 detail Dom.jpg – Wikimedia Commons

‘Cathedral thinking’ may also result in something a little less glamorous than the Notre Dame. In the face of the ‘great stink’ crisis of 1848, Joseph Bazalgette designed the trailblazing London sewerage system with the future in mind, giving his tanks the capacity to withstand the doubling of the city’s population. What he built was perhaps not the cheapest possible solution to the problem, but was something sturdy and strong that lasted well-beyond his lifetime. We’ve not experienced another ‘great stink’ since.

There are also plenty of innovative cultural and scientific projects in progress today that show what long-termism could look like in action. Take the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, a facility built deep into the Arctic permafrost that houses 1.2 million seeds from plants found across the planet. Its content, which is frozen – literally – into eternity, is designed to withstand natural disasters and human destruction. Perhaps, one day, in 100, or 100,000 years, the seed vault will prove to be our insurance policy against existential catastrophe. “It is a bit like being in a cathedral”, says Lise Lykke Steffensen, executive director of the company responsible for the day-to-day operation of the vault. “All you can hear is yourself”.

The Svalbard Global Seed Vault. The epitome of long-term thinking. Source: Crop Seed on Flickr

The way forward

The common thread which links all these vastly different projects – both past and present – is a kind of selflessness, or an ability to see beyond one’s own immediate context. Admittedly, it is difficult not to feel as though they are anomalies – mere disruptions to the prevailing culture of short termism. However, these intentional acts of care and stewardship of the future – immortalised in great medieval cathedrals, robust sewerage systems, and innovative scientific projects – show that a different path is possible.

To embark on this path, we must reorient our relationship to future generations and be prepared to take on projects and policies whose main benefits may not actually be seen in the short-term. To invoke that famous proverb, we will only be able to meet the challenges of the world to come if we are willing to plant trees in the shade of which we will never sit. To tackle what Roman Krznaric – author of ‘The Good Ancestor’, a brilliant book on long-termism – calls the “conceptual emergency” of short-sightedness, it is vital that we realise that our current predicament is not inescapable. Rather, as we have seen, there exists an alternative way of thinking, one that may prove to be an essential tool as we approach the crossroads of our infinitely vast, wildly unpredictable future.

Further resources

‘The Cathedral Thinkers’, BBC Radio 4 – A short but sweet radio programme on the possibilities of ‘cathedral thinking’

‘The Good Ancestor’ by Roman Krznaric – A brilliant, accessible book outlining long-termism as a philosophy and practise.

The Long Now Foundation – A non-profit organisation that seeks to promote long-term thinking. The foundation has several ongoing projects, including a 10,000-year clock known as the Clock of the Long Now. There are plenty of interesting blog posts and recorded seminars and lectures on their website

‘Into Eternity’ – a 2010 documentary by Danish filmmaker Michael Madsen about Finland’s long term nuclear waste repository ‘Onkalo’, the first of its kind in the world.