The GDP figure, as has been the norm for many years, was below the UK’s but actually looked a bit better compared to the years when I covered it as a journalist.

So I asked why that was. “The bridge,” he replied and pointed out of the window in the general direction of the Queensferry Crossing, then being built across the Firth of Forth adding, “The problem is we can’t just keep on rely on building big bridges.”

At the time, the SNP were into their second term as the Scottish Government and large scale projects such as the new bridge, the M74 extension and Aberdeen by-pass had boosted Scotland’s GDP – even if the latter two were products of the previous Labour-Lib Dem coalition.

Fast forward to 2021. The bridges and roads are complete but Scotland’s GDP is still stuck in a lay-by.

The figure for annual GDP growth for the whole of 2019 was 0.7%. The UK figure was 1.4%.

Scotland’s productivity is poor and its business birth rate is among the worst in the UK.

Regardless of whether Scotland is part of the union or independent, it’s clear the economy faces significant challenges that need resolving, a fact both sides of the debate should remember.

After 14 years in power, the SNP hasn’t shifted Scotland’s growth rate or business start-up figure to anything like something that would suggest Scotland is the next Celtic Tiger.

That may not have done them much damage at the ballot box but the pressure is building on a number of fronts.

The entrepreneur and philanthropist Sir Tom Hunter has long been an advocate of policies to boost wealth creation in Scotland and the recent report from his Hunter Foundation highlighted the lack of progress in achieving that ambition.

The report’s aim was to address such issues as low productivity, poor business birth rate and lack of success with scale-ups that help to explain why Scotland’s GDP per head is far behind similar sized countries. It forecast that without significant change, from 2020 to 2035, Scottish real GDP growth will average just 1.3%

Among its proposals were increases in government borrowing to stimulate stronger growth, significant tax cuts and deregulation and large increases in government support for businesses. But will any of that happen?

There is a perception that under Nicola Sturgeon, the Scottish Government doesn’t have the same interest in wealth creation and economic development as was the case in previous years and that her focus is more on tackling social and health issues.

In the SNP manifesto, you had to wait until page 44 to get to the economic vision, though to be fair once you got there it was still more coherent than anything from the other parties.

Critics point out that Scotland has higher personal tax rates for people at the top end than the rest of the UK and a development agency that’s a poor shadow of its former self. It’s now more than a curiosity that the Scottish Government has been without a dedicated economy minister since early 2020.

Recent internal polling for the SNP is believed to have shown the economy is now a much bigger priority for voters and may even rank ahead of health and education in importance.

That may partly be explained by a feeling that the worst of the Covid crisis is behind us and now the worry is about jobs, growth and pay packets. And there’s no doubt that during the current campaign there’s been as much emphasis on a new approach to economic matters as health and education.

The SNP unveiled plans for a £50m National Challenge competition seeking an idea that could transform the economy . The party has also proposed a number of initiatives to boost digital access and infrastructure.

The reason for this shift may be the need to convince voters of the viability of an independent Scotland even if the SNP’s views on economics of independence remain somewhat of a mystery.

Sturgeon tried to brush off persistent questioning from Channel 4’s Ciaran Jenkins on whether the SNP had analysed the cost of separation by saying it would be set out before a referendum, while basically dismissing her own Sustainable Growth Commission’s report as out of date.

Is that position credible?

The SNP may be leaving independence off election leaflets but they are still treating this poll as the way to give them a mandate for a new referendum.

Building economic credibility, as well as having someone credible to front the plan, will be crucial to persuading swing voters.

In the early days of the Scottish Parliament, Jim Mathers was the enthusiastic front man for its business policies. At times he seemed a slightly odd but likeable figure, permanently optimistic and obsessed with mind maps but his admirable persistence paid off and by the time they came to power in 2007 it is arguable to say they were much more credible than Labour and the Tories with much of business.

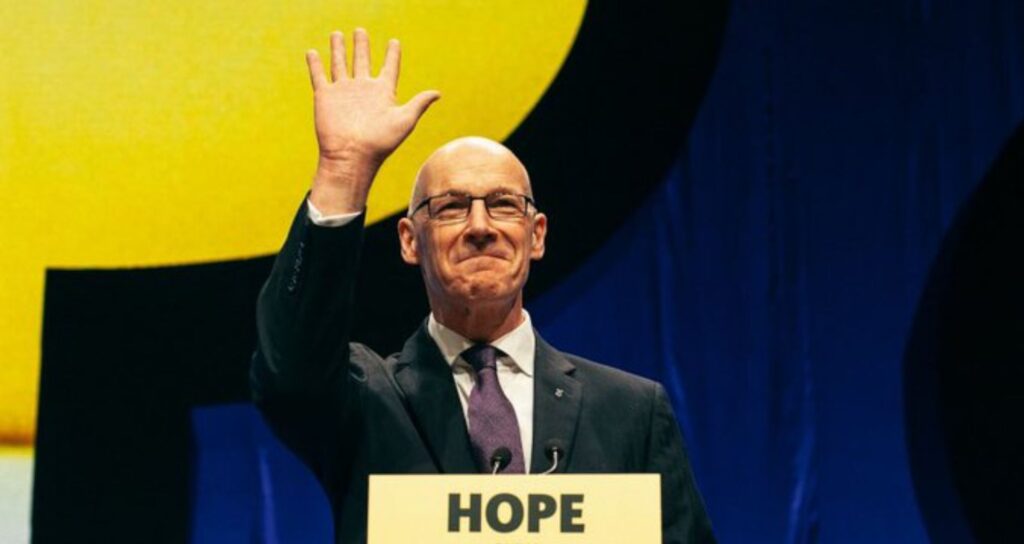

That position, however, has been slipping away since John Swinney departed the economic brief. Since the Deputy First Minister moved to education, the Scottish Government hasn’t managed to replace his ability to have an honest, credible and pragmatic dialogue with the business community over the economic challenges facing the country.

In the wake of Derek Mackay’s departure in disgrace, Sturgeon turned to trusted colleague Fiona Hyslop who added the economy brief to her already broad portfolio with little obvious enthusiasm.

And there’s a very small circle of ‘safe’ business figures wheeled out to chair reports or lead new investment vehicles -with another one, a new “National Infrastructure Company” promised this time round — but sometimes that circle is so small it seems to be the same person time after time.

If the SNP form a Government in May, it will be interesting to see the shape of the new Cabinet.

The Finance Secretary Kate Forbes is undoubtedly a rising star and been tipped as a possible future leader by Sturgeon herself, but the Party still needs to prove there is a deliverable economic vision beyond the rhetoric.

Perhaps the heart of the issue isn’t the person behind it but whether the long term economic vision is credible and will have a positive effect on GDP.

In the manifesto there is a short paragraph suggesting that they would look at building a new bridge over the Clyde between Gourock and Dunoon. That would be at least as long and possibly more complicated than the 1.7 mile Queensferry Crossing which cost £1.35bn.

Maybe they can just keep building bridges after all.

John Penman, Partner, 56˚ North